(Visual) Notes on Culture

7/30/2006

The Total Artist Film: EDVARD MUNCH

After making a handful of excellent amateur films, Peter Watkins jumped head-first into the international film and TV scene with Culloden (1964). The critical and popular success of that historical telefilm, which dynamized one of the key battles in British history, lead to the realization of his urgent pet-project: The War Game (1966). The intriguing and sordid tale of that production is best saved for another day - regardless, it soured Watkins' taste for conventional media channels.

He permanently relocated to Sweden in the early 1970s (he made The Gladiators there in 1969 but then ventured to the United States for the incendiary Punishment Park). All of his work challenges assumptions about viewing positions, the relationship between history and visual representation, and the broadest possible conceptions of objectivity/subjectivity.

Edvard Munch (1975) is considered his best work, and for good reason. I cannot think of another artist film besides Ken Russell's Savage Messiah (1972) that does so good a job at encapsulating, investigating, and explaining the life of a creative genius in the visual arts.

Munch lead a tortured life. He was at odds with the conservative art world of Norway and too morose for other circles on the continent. His circle in Berlin often cast him to the periphery. Beyond all else, his art was haunted by memory - the memory of the tragic health of his family members and the memory of the lost love of a woman.

Watkins literally places himself into Munch's world - he provides powerful narration, but also configures the story to mirror his own experience. Munch was at odds with the critical establishment, was forced to "check" his artistic ambitions as a young man (Watkins' War Game), and endured a continual chastising for his techniques.

The story of Munch's life is not strictly chronological, but rather dialogical. Images of various eras of the man's life are often thrown together with intensity. Munch's art is the result of genius, madness, and memory. The narration of Watkins mixes with direct interviews. The characters in the story often look into the camera, in both confusion and sincerity. As viewers, we are implicated - we must feel Munch's pain and address the montage of his life.

Watkins goes one further and captures the techniques and textures of Munch in presenting his story. Munch's canvases were known for their expressive quality. His willingness to scratch his paintings , mix oil with egg tempra, or even use unprimed canvases, gives his work a powerful aura. Watkins utlizes grainy stocks, zooms, and often allows the camera to lapse into and out of focus. The result is a close approximation to the murky membrane over many of Munch's paintings.

Click here for an interview with Watkins.

After making a handful of excellent amateur films, Peter Watkins jumped head-first into the international film and TV scene with Culloden (1964). The critical and popular success of that historical telefilm, which dynamized one of the key battles in British history, lead to the realization of his urgent pet-project: The War Game (1966). The intriguing and sordid tale of that production is best saved for another day - regardless, it soured Watkins' taste for conventional media channels.

He permanently relocated to Sweden in the early 1970s (he made The Gladiators there in 1969 but then ventured to the United States for the incendiary Punishment Park). All of his work challenges assumptions about viewing positions, the relationship between history and visual representation, and the broadest possible conceptions of objectivity/subjectivity.

Edvard Munch (1975) is considered his best work, and for good reason. I cannot think of another artist film besides Ken Russell's Savage Messiah (1972) that does so good a job at encapsulating, investigating, and explaining the life of a creative genius in the visual arts.

Munch lead a tortured life. He was at odds with the conservative art world of Norway and too morose for other circles on the continent. His circle in Berlin often cast him to the periphery. Beyond all else, his art was haunted by memory - the memory of the tragic health of his family members and the memory of the lost love of a woman.

Watkins literally places himself into Munch's world - he provides powerful narration, but also configures the story to mirror his own experience. Munch was at odds with the critical establishment, was forced to "check" his artistic ambitions as a young man (Watkins' War Game), and endured a continual chastising for his techniques.

The story of Munch's life is not strictly chronological, but rather dialogical. Images of various eras of the man's life are often thrown together with intensity. Munch's art is the result of genius, madness, and memory. The narration of Watkins mixes with direct interviews. The characters in the story often look into the camera, in both confusion and sincerity. As viewers, we are implicated - we must feel Munch's pain and address the montage of his life.

Watkins goes one further and captures the techniques and textures of Munch in presenting his story. Munch's canvases were known for their expressive quality. His willingness to scratch his paintings , mix oil with egg tempra, or even use unprimed canvases, gives his work a powerful aura. Watkins utlizes grainy stocks, zooms, and often allows the camera to lapse into and out of focus. The result is a close approximation to the murky membrane over many of Munch's paintings.

Click here for an interview with Watkins.

7/27/2006

Quote of the Week: Theory

"Conventional English literary criticism has tended to divide into two camps over structuralism. On the one hand there are those who see in it the end of civilization as we have known it. On the other hand, there are those erstwhile or essentially conventional critics who have scrambled with varying degrees of dignity on a bandwagon which in Paris at least has been disappearing down the road for some time. The fact that structuralism was effectively over as an intellectual movement in Europe some years ago has not seemed to deter them: a decade or so is perhaps the customary time-lapse for ideas in transit across the Channel. These critics operate, one might say, rather like intellectual immigration officers: their job is to stand at Dover as the new-fangled ideas are unloaded from Paris, examine the bits and pieces which seem more or less reconcilable with traditional critical techniques, wave these goods genially on and keep out of the country the rather more explosive forms of equipment (Marxism, feminism, Freudianism) which have arrived with them. Anything unlikely to prove distasteful in the middle-class suburbs is supplied with a work permit; less well-heeled ideas are packed back on the next boat."

- Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction, pp.106-107

- Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction, pp.106-107

Produce a Film for Alex Cox

Severely underappreciated filmmaker Alex Cox needs your help. His latest project, Searchers 2.0, is all set to role out, but it needs money. Cox is no stranger to the perils of the international co-production: his masterpiece Three Businessmen (1998) was partially financed by a Dutch philosopher, while his adaptation of Death and the Compass (1996) is a co-production of three countries. His latest blog post details the current status of his latest film. For the low, low price of $130,000+, you finance roughly half of his movie! Smaller chunks of "producer points" are also available.

This project will likely go one of two ways. On the one hand, it could (if successful), illustrate new potential avenues for aspiring filmmakers and those willing to act as patrons. On the other, it could have 50+ associate producers and have credits that read like the list of onering.net fans on the Lord of the Rings films. Though Cox does have his fans (I am one of them, and continue to contend that he is one of the most consistently engaging contemporary filmmakers), he probably does not have enough with that kind of money. Here's hoping that he finds that rich venture capitalist with an eye for quality and a heart.

This project will likely go one of two ways. On the one hand, it could (if successful), illustrate new potential avenues for aspiring filmmakers and those willing to act as patrons. On the other, it could have 50+ associate producers and have credits that read like the list of onering.net fans on the Lord of the Rings films. Though Cox does have his fans (I am one of them, and continue to contend that he is one of the most consistently engaging contemporary filmmakers), he probably does not have enough with that kind of money. Here's hoping that he finds that rich venture capitalist with an eye for quality and a heart.

7/21/2006

Quote of the Week: Celebrity

"Jean-Luc Godard, having fallen out with the curators of his Pompidou Center retrospective and art installation, is reported to have told one of them, 'Now you can commit suicide.'"

Film Comment, July-August 2006, p. 8

Film Comment, July-August 2006, p. 8

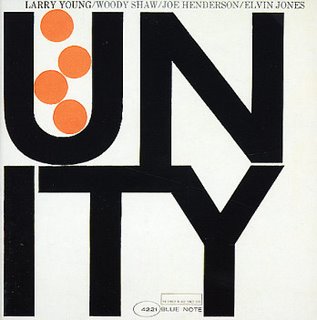

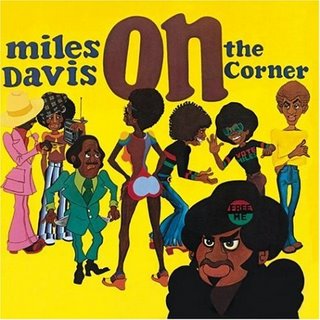

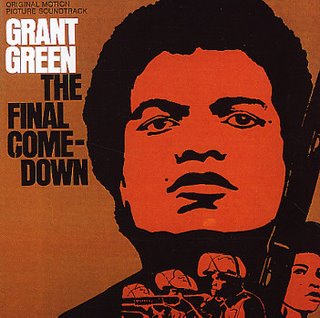

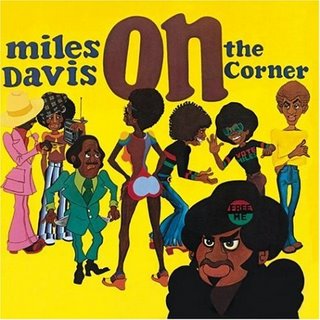

Iconic Jazz Album Design

Miles Davis - On the Corner

Miles Davis - On the Corner

Album cover art serves to illuminate and sell the packaged music. Often times it panders to the worst possible ideas. Often, these images can innovate. Below are four works that take aspects of the jazz aesthetic of their musicians and say something beyond the norm.

Miles Davis - On the Corner

Miles Davis - On the Corner

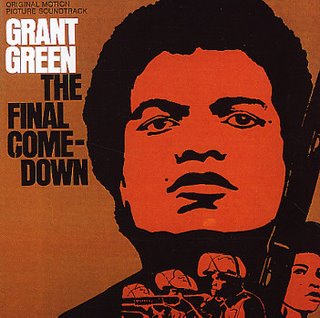

Grant Green - Soundtrack to The Final Comedown

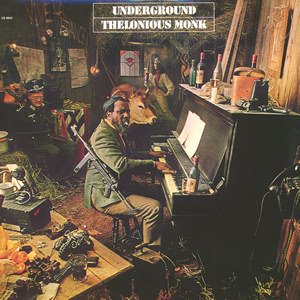

Thelonious Monk - Underground

Blue Note Records has released a book that highlights some other great selections.

7/17/2006

Reading Surrealism: A View of NADJA

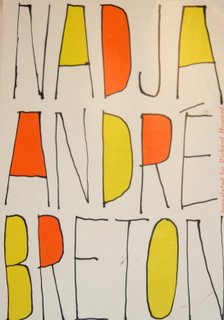

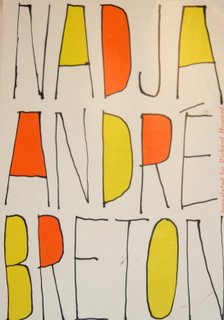

Nadja ~ Andre Breton (1928, trans. Richard Howard, 1960)

Nadja ~ Andre Breton (1928, trans. Richard Howard, 1960)

"With this system which consists, before going into a movie theater, of never looking to see what's playing - which, moreover, would scarcely do me any good, since I cannot remember the names of more than five or six actors - I obviously run the risk of missing more than others, though here I must confess my weakness for the most absolutely absurd French films. I understand, moreover, quite poorly, I follow too vaguely." - p. 37

Andre Breton does a great service to the readers of Nadja, known as one of the great surrealist romances (yes, it is a sub, subgenre), by leaking some mapping strategies that provide ready areas of entry for his seemingly oblique evocation. Understanding Nadja is not about mentally ordering narrative and desperately recalling character names, but rather akin to a leisurely stroll in a city. The reader benefits from image and text, as photographs are used to accompany the text at certain moments. The "story" is simple: our author meets a mysterious woman named Nadja whom he finds extraoridinary, but she soon leaves it.

My summary is light on details, but for a reason. Breton and the surrealists swear by dream logic. In dreams, linear stories are often impossible to remember once the head is lifted from the pillow. What usually lingers are a bizarre set of details. Thus, Breton fleshes out his tale by emphasizing the powerful emotional intensities that can mean far more than the cut and dry of an event. The road map he leaves is laid out in the openning portion of the book. Rather than launch immediately into his meeting Nadja, the author writes an initial, suspect "auto" biography. Here, Breton's committment is evident. Going to the theatre does not provoke the usual set of meanings, but rather observations like "the ridiculous acting of the performers, who paid only the faintest attention to their parts, scarcely listening to each other and busy making dates with members of the audience, which consisted of perhaps fifteen people at most, always reminded me of a canvas backdrop" (38). The spaces and places of Paris are not significant for their use-value, but rather the way that they "strike": "the statue of Etienne Dolet on its plinth in the Place Maubert in Paris has always fascinated me and induced unbearable discomfort..." (24).

Breton strings incidental phenomena into a narrative, in the process guiding the reader to string the "striking" incidents into their own, puzzling, experience. I found myself intrigued by the phrasing, uncertainty, indeed the mystery of Breton's language at times more than the mystery of Nadja. To illustrate what compells me:

Predella of the Profanation of the Host: The Jewish Pawnbroker Roasting the Consecrated Host in the Fire Which Streams with Blood Arousing the Attention of the Bailiffs who Batter Down the Door, Paolo Uccello, 1468.

Predella of the Profanation of the Host: The Jewish Pawnbroker Roasting the Consecrated Host in the Fire Which Streams with Blood Arousing the Attention of the Bailiffs who Batter Down the Door, Paolo Uccello, 1468.

At one point during the author's account of his interactions with Nadja, he recalls receiving a letter that contains a photograph of this image. In a footnote, he says "I saw it [the painting] reproduced in its entirety only several months later. It seemed to me full of hidden intentions, and, in all respects, quite difficult to interpret." This passage summarizes the experience of Nadja for me. The small details, incidental assides, and seemingly unimportant utterances become the real center of meaning. The hidden intentions of Nadja seem to have to do with showing how Breton was able to give his abilities of free association the will to trimuph over convention, and how by following his example, a reader can begin to decode even the most obscure and obscuring meanings that confront them.

Nadja ~ Andre Breton (1928, trans. Richard Howard, 1960)

Nadja ~ Andre Breton (1928, trans. Richard Howard, 1960)"With this system which consists, before going into a movie theater, of never looking to see what's playing - which, moreover, would scarcely do me any good, since I cannot remember the names of more than five or six actors - I obviously run the risk of missing more than others, though here I must confess my weakness for the most absolutely absurd French films. I understand, moreover, quite poorly, I follow too vaguely." - p. 37

Andre Breton does a great service to the readers of Nadja, known as one of the great surrealist romances (yes, it is a sub, subgenre), by leaking some mapping strategies that provide ready areas of entry for his seemingly oblique evocation. Understanding Nadja is not about mentally ordering narrative and desperately recalling character names, but rather akin to a leisurely stroll in a city. The reader benefits from image and text, as photographs are used to accompany the text at certain moments. The "story" is simple: our author meets a mysterious woman named Nadja whom he finds extraoridinary, but she soon leaves it.

My summary is light on details, but for a reason. Breton and the surrealists swear by dream logic. In dreams, linear stories are often impossible to remember once the head is lifted from the pillow. What usually lingers are a bizarre set of details. Thus, Breton fleshes out his tale by emphasizing the powerful emotional intensities that can mean far more than the cut and dry of an event. The road map he leaves is laid out in the openning portion of the book. Rather than launch immediately into his meeting Nadja, the author writes an initial, suspect "auto" biography. Here, Breton's committment is evident. Going to the theatre does not provoke the usual set of meanings, but rather observations like "the ridiculous acting of the performers, who paid only the faintest attention to their parts, scarcely listening to each other and busy making dates with members of the audience, which consisted of perhaps fifteen people at most, always reminded me of a canvas backdrop" (38). The spaces and places of Paris are not significant for their use-value, but rather the way that they "strike": "the statue of Etienne Dolet on its plinth in the Place Maubert in Paris has always fascinated me and induced unbearable discomfort..." (24).

Breton strings incidental phenomena into a narrative, in the process guiding the reader to string the "striking" incidents into their own, puzzling, experience. I found myself intrigued by the phrasing, uncertainty, indeed the mystery of Breton's language at times more than the mystery of Nadja. To illustrate what compells me:

Predella of the Profanation of the Host: The Jewish Pawnbroker Roasting the Consecrated Host in the Fire Which Streams with Blood Arousing the Attention of the Bailiffs who Batter Down the Door, Paolo Uccello, 1468.

Predella of the Profanation of the Host: The Jewish Pawnbroker Roasting the Consecrated Host in the Fire Which Streams with Blood Arousing the Attention of the Bailiffs who Batter Down the Door, Paolo Uccello, 1468.At one point during the author's account of his interactions with Nadja, he recalls receiving a letter that contains a photograph of this image. In a footnote, he says "I saw it [the painting] reproduced in its entirety only several months later. It seemed to me full of hidden intentions, and, in all respects, quite difficult to interpret." This passage summarizes the experience of Nadja for me. The small details, incidental assides, and seemingly unimportant utterances become the real center of meaning. The hidden intentions of Nadja seem to have to do with showing how Breton was able to give his abilities of free association the will to trimuph over convention, and how by following his example, a reader can begin to decode even the most obscure and obscuring meanings that confront them.

7/14/2006

Quote of the Week: Literature

Seem Chaos, be resolved to order’s sway,

And error’s night be turned to virtue’s day –

~ Percy Bysshe Shelley, Poetical Essay, 1811

A great find for Shelley scholars

And error’s night be turned to virtue’s day –

~ Percy Bysshe Shelley, Poetical Essay, 1811

A great find for Shelley scholars

7/13/2006

Book Review: THE BRITISH CINEMATOGRAPHER

The British Cinematographer

The British Cinematographer

Duncan Petrie ~ 1996

BFI Publishing

Hardcover: $49.95

Softcover: $22.50

The British Cinematographer is an How the Other Half Lives for the film set: it provides an alternate, technical history of British cameramen, downplaying the historical and critical tendency to default onto a film's director, instead talking about the life and work of these unsung heroes of the movies. Petrie's work consists of two main parts. He begins with a narrative survey that historicizes the major technoligical developments that coincided with the conventionally known groupings/movements in British film history. This approach yields a certain, necessary re-imagining of the great names of England's cinema - the beauty of David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962) is also very much because of Freddie Young's dilligence and experience, while the successful aesthetic of Derek Jarman's Edward II (1991) owes technical realization to Ian Wilson. One of the recurring stories for British cinematographers is their utter dependency of America, whether it be for stylistic precursors, technical mastery, or, starting in the mid 1970s, as a place to work. In the early days of the British studios, well after the established excellence of the Hollywood model, cinematographers had to assimilate most of their technical know-how from Americans, who were the only ones with access to sufficently excellent equipment.

Part II contains profiles of the major players. The book's greatest flaw, which is dutifully acknowledged, are its space constraints. Petrie was only able to include a relatively limited number of bios, amounting to a good smattering of the most prolific or memorable cameramen from each era. Likewise, most of the people he talks about excelled in the naturalist/realist school, but to be fair, much British film placed a particular emphasis on this presentational mode.

The British Cinematographer can be read quickly for its alternate history of British cinema, but later used as a reference guide for rectifying the general scholarly neglect toward cameramen.

The British Cinematographer

The British CinematographerDuncan Petrie ~ 1996

BFI Publishing

Hardcover: $49.95

Softcover: $22.50

The British Cinematographer is an How the Other Half Lives for the film set: it provides an alternate, technical history of British cameramen, downplaying the historical and critical tendency to default onto a film's director, instead talking about the life and work of these unsung heroes of the movies. Petrie's work consists of two main parts. He begins with a narrative survey that historicizes the major technoligical developments that coincided with the conventionally known groupings/movements in British film history. This approach yields a certain, necessary re-imagining of the great names of England's cinema - the beauty of David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962) is also very much because of Freddie Young's dilligence and experience, while the successful aesthetic of Derek Jarman's Edward II (1991) owes technical realization to Ian Wilson. One of the recurring stories for British cinematographers is their utter dependency of America, whether it be for stylistic precursors, technical mastery, or, starting in the mid 1970s, as a place to work. In the early days of the British studios, well after the established excellence of the Hollywood model, cinematographers had to assimilate most of their technical know-how from Americans, who were the only ones with access to sufficently excellent equipment.

Part II contains profiles of the major players. The book's greatest flaw, which is dutifully acknowledged, are its space constraints. Petrie was only able to include a relatively limited number of bios, amounting to a good smattering of the most prolific or memorable cameramen from each era. Likewise, most of the people he talks about excelled in the naturalist/realist school, but to be fair, much British film placed a particular emphasis on this presentational mode.

The British Cinematographer can be read quickly for its alternate history of British cinema, but later used as a reference guide for rectifying the general scholarly neglect toward cameramen.

Museums and Access: Risings Costs, Splintered Attendence?

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City has quietly raised its suggested adult entrance fee from $15 to $20, effective August 1st. An on-going budget deficit was cited as the main reason.

Bear in mind that this is merely a suggested donation - but, with that in mind, think of the hostility and scorn potentially brought down by museum staff on people of able means who short-change the museum. The realities of running a museum, including their operating costs, staffing issues, and requirments as cultural institutions with a necessarily stringent lists of standards, is now at odds with the issue of access, or the ultimate raison d'etre of providing a service to an interested public.

The possible problems abound. In their provacative study The Value of Things, Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska provide a detailed of analysis of the ways in which withheld access and information could plague the experience of visiting museum spaces (in their case, results are drawn from a lengthy assessment of the operating procedures of the British Museum). Among other things, they notice the already-existing wealth and class hurdles of museums, as well as their ability to cold-shoulder data to even the most veteran researchers.

Arts education demands a certain amount of "being there" that the Met will no longer be able to guarentee. Though other options exist - in the form of digital curatorship and excursions to online galleries - prohibitive entrance costs could endanger the primary experience of the visual arts for a large number of people. But this begs an even bigger, and no less urgent question: "How can the art world in America survive with ever-dwindling governmental support?"

Bear in mind that this is merely a suggested donation - but, with that in mind, think of the hostility and scorn potentially brought down by museum staff on people of able means who short-change the museum. The realities of running a museum, including their operating costs, staffing issues, and requirments as cultural institutions with a necessarily stringent lists of standards, is now at odds with the issue of access, or the ultimate raison d'etre of providing a service to an interested public.

The possible problems abound. In their provacative study The Value of Things, Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska provide a detailed of analysis of the ways in which withheld access and information could plague the experience of visiting museum spaces (in their case, results are drawn from a lengthy assessment of the operating procedures of the British Museum). Among other things, they notice the already-existing wealth and class hurdles of museums, as well as their ability to cold-shoulder data to even the most veteran researchers.

Arts education demands a certain amount of "being there" that the Met will no longer be able to guarentee. Though other options exist - in the form of digital curatorship and excursions to online galleries - prohibitive entrance costs could endanger the primary experience of the visual arts for a large number of people. But this begs an even bigger, and no less urgent question: "How can the art world in America survive with ever-dwindling governmental support?"

7/11/2006

Film Review: ORCHESTRA REHEARSAL

Prova d'orchestra/Orchestra Rehearsal ~ 1978 ~ Written and Directed by Federico Fellini

Prova d'orchestra/Orchestra Rehearsal ~ 1978 ~ Written and Directed by Federico Fellini

Orchestra Rehearsal is not technically a "film" (it was made for West German television, though shot on film) and inhabits one of the conventionally agreed upon "lesser" stations of the maestro's work. Similar in scope and technique to his other inventive television documentaries (Fellini: A Director's Notebook and The Clowns), Orchestra Rehearsal blurs the distinctions of fantasy and objectivity that distinguishes the greatest "counter-factual" documentary work. Though styled after a documentary, in this case Fellini presents a tale of social and economic unrest that is contained within the seemingly innocuous focus on the practice habits of a minor orchestra.

In the process, we witness an epic struggle mounting between the unionized musicians (who range from the nostalgic/contented harp player to some anarchic young firebrands) and the conductor. The conductor character emits terrible authority in the grand continental tradition, invoking thoughts of Wagner and other mad geniuses. The extreme tensions that mount, capped by a Lord of the Flies style frenzy, typify the Fellinian world view. This relatively short film serves as more of an allegory for an embedded distrust circulating among different generations of Europeans, recovering from the shadowing crises of the Second World War and the movements toward revolution of the 1960s.

Taken as a whole, Fellini manages to shatter the myth of the orchestra-unit as a bastion of sanctity for the so-called serious arts. Though this T.V. effort lacks some of his trademark inventiveness until the very end, and despite its relatively limited scope, it reminds of a time when international co-productions on television yielded interesting results.

Prova d'orchestra/Orchestra Rehearsal ~ 1978 ~ Written and Directed by Federico Fellini

Prova d'orchestra/Orchestra Rehearsal ~ 1978 ~ Written and Directed by Federico FelliniOrchestra Rehearsal is not technically a "film" (it was made for West German television, though shot on film) and inhabits one of the conventionally agreed upon "lesser" stations of the maestro's work. Similar in scope and technique to his other inventive television documentaries (Fellini: A Director's Notebook and The Clowns), Orchestra Rehearsal blurs the distinctions of fantasy and objectivity that distinguishes the greatest "counter-factual" documentary work. Though styled after a documentary, in this case Fellini presents a tale of social and economic unrest that is contained within the seemingly innocuous focus on the practice habits of a minor orchestra.

In the process, we witness an epic struggle mounting between the unionized musicians (who range from the nostalgic/contented harp player to some anarchic young firebrands) and the conductor. The conductor character emits terrible authority in the grand continental tradition, invoking thoughts of Wagner and other mad geniuses. The extreme tensions that mount, capped by a Lord of the Flies style frenzy, typify the Fellinian world view. This relatively short film serves as more of an allegory for an embedded distrust circulating among different generations of Europeans, recovering from the shadowing crises of the Second World War and the movements toward revolution of the 1960s.

Taken as a whole, Fellini manages to shatter the myth of the orchestra-unit as a bastion of sanctity for the so-called serious arts. Though this T.V. effort lacks some of his trademark inventiveness until the very end, and despite its relatively limited scope, it reminds of a time when international co-productions on television yielded interesting results.

A new Guggenheim?

Guggenheim museums (locations in Venice, Berlin, Las Vegas, Bilbao, and New York) are about to have an interesting encounter with the Islamic world. It has recently been announced that Frank Gehry will design a new sturcture, which is tentatively set to open in 2011 in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emerates.

So what? The UAE is known for its toursim, but not necessarily for its cutting-edge adherence to the principles of contemporary art. Early speculations predict a very difficult and uneasy future of ultra-conservative Islamic self-censorship (or evident disgust at what hostile matter manages public exhibition) clashing with some art and artists who labor with sexual issues. The structure will probably not house works by, say, Francis Bacon or Cindy Sherman. But can it be continent with work entirely within the Islamic decorative tradition, or failing just that, abstract/non-representational works without enough form to offend? The goal is apparently to foster "cultural exchange," but as recent events in the Netherlands show, that desire is slightly harder to attain than to talk about. If the museum attracts enough of an international, (rich), and demanding clientele, then perhaps it will provide a chance to test the meddle of both east and west.

More can be found here:

No nudes in world's biggest Guggenheim?

So what? The UAE is known for its toursim, but not necessarily for its cutting-edge adherence to the principles of contemporary art. Early speculations predict a very difficult and uneasy future of ultra-conservative Islamic self-censorship (or evident disgust at what hostile matter manages public exhibition) clashing with some art and artists who labor with sexual issues. The structure will probably not house works by, say, Francis Bacon or Cindy Sherman. But can it be continent with work entirely within the Islamic decorative tradition, or failing just that, abstract/non-representational works without enough form to offend? The goal is apparently to foster "cultural exchange," but as recent events in the Netherlands show, that desire is slightly harder to attain than to talk about. If the museum attracts enough of an international, (rich), and demanding clientele, then perhaps it will provide a chance to test the meddle of both east and west.

More can be found here:

No nudes in world's biggest Guggenheim?

7/10/2006

Quote of the Week: Television and Popular Culture

"A further dilemma with the present TV and cinema popular culture - one for which many educators share a prime responsibility - is that it continues to exist as one large, gross and crude form, without complexity, subtlety or variety. For decade after decade, its output and manner of representation, its language-form and themes, have remained within rigid hierarchical boundaries. Commercialism and pandering to voyeurism remain its central pillars. It is also very important to note that not all people want the popular culture - at least not in its present simplistic, narrow, often very brutal form."

~ Peter Watkins

For more: The teaching of popular culture

~ Peter Watkins

For more: The teaching of popular culture

Book Review: A GREAT, SILLY GRIN: THE BRITISH SATIRE BOOM OF THE 1960S

A Great, Silly Grin: The British Satire Boom of the 1960s

A Great, Silly Grin: The British Satire Boom of the 1960s

Humphrey Carpenter ~ 2000/2003

Public Affairs/Da Capo

Hardcover: $27.50

Softcover: $19.95

British comedy and the varities of its sources of humor are regarded as an autonomous subgenre by many in the United States. Whether or not this view is correct (and indeed, Humphrey Carpenter addresses it with breadth and deft analysis) seems inconsecquential next to the larger question of "How did comedy (in Western industrial nations) manage to transcend the grim limitations of a staid post-war culture and form a key element of worldwide rebellion?"

Carpenter's narrative goes a long way into explaining how a relatively isolated movement in comedy, part and parcel to broader trends in a culture ready to burst, had a profound effect on the people of its day and formed a bedrock foundation for later expressions of satire, parody, and its bretheren. Long before the stylized burlesque of Saturday Night Live (1975 - present) on one side of the Atlantic and the madcap surrealism of Monty Python's Flying Circus (1969 - 1974) on the other, a group of young men from a variety of societal vantage points formed a new kind of revue, first presented at the Edinbrugh Festival as Beyond the Fringe in 1959. British stage comedy had long been dominated by light cabaret, the most challenging and out-there examples of which were found in the private "smoker" revues at Oxford and Cambridge that brought acidic wit and scathing humor to a select, very homogenous, and largely drunk audience. Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, and Jonathan Miller augmented this tradition by blending the sophmoric humor of the past with pointed, controlled, and darring political satire that spoke directly to the moment. Their success at Edinbrugh set-off a "satire boom" that tested the long standing cultural institutions of censorship, libel and slander. Revues were just the beginning: the satircal rag Private Eye, a fashionable club called The Establishment, the controversal BBC show This Was the Week that Was, and some landmark cross-pollination with performers from the United States (Lenny Bruce in particular) took comedy in many new diretions. The resultant legacy paved the way for the proliferation of comedic expression of the next few decades - some, including Carpenter, would suggest an abundant over-proliferation - and allowed most of the personalities involved to have meaningful careers in television and film.

Carpenter knows the bold task before him: rescue an under-researched period of British cultural history from obscurity, in the process convincing many of its principle players that their achievements were far more significant than even they thought, all while staying within the confides of defensible scholarship. For the most part, he does a wonderful job. The stories of how satire rose and fell are mostly culled from anecdotal chimings by the comedians under scrutiny, but at times their memories leave cloudy pictures of what really happened. In the end, the possibilities of satire are but one part of a larger matrix that included the literature of the "Angry Young Men," the films of the (confusingly, perhaps unfairly named) British New Wave, the fallout of cultural revolutions of various stripes, and a general youthful world-view that supercedes the dreary past. His defense of the histories of the satirists against, say, the filmmakers (toward the end of the book) seems a little unwarranted. He need not question the value of his work, but rather, if any major criticism could be levelled against it, could have continually weaved a broader cultural web instead of leaving it all for the end. Recommended reading for persons interested in British cultural history, the history of comedy, and narratives of success in the arts.

A Great, Silly Grin: The British Satire Boom of the 1960s

A Great, Silly Grin: The British Satire Boom of the 1960sHumphrey Carpenter ~ 2000/2003

Public Affairs/Da Capo

Hardcover: $27.50

Softcover: $19.95

British comedy and the varities of its sources of humor are regarded as an autonomous subgenre by many in the United States. Whether or not this view is correct (and indeed, Humphrey Carpenter addresses it with breadth and deft analysis) seems inconsecquential next to the larger question of "How did comedy (in Western industrial nations) manage to transcend the grim limitations of a staid post-war culture and form a key element of worldwide rebellion?"

Carpenter's narrative goes a long way into explaining how a relatively isolated movement in comedy, part and parcel to broader trends in a culture ready to burst, had a profound effect on the people of its day and formed a bedrock foundation for later expressions of satire, parody, and its bretheren. Long before the stylized burlesque of Saturday Night Live (1975 - present) on one side of the Atlantic and the madcap surrealism of Monty Python's Flying Circus (1969 - 1974) on the other, a group of young men from a variety of societal vantage points formed a new kind of revue, first presented at the Edinbrugh Festival as Beyond the Fringe in 1959. British stage comedy had long been dominated by light cabaret, the most challenging and out-there examples of which were found in the private "smoker" revues at Oxford and Cambridge that brought acidic wit and scathing humor to a select, very homogenous, and largely drunk audience. Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, and Jonathan Miller augmented this tradition by blending the sophmoric humor of the past with pointed, controlled, and darring political satire that spoke directly to the moment. Their success at Edinbrugh set-off a "satire boom" that tested the long standing cultural institutions of censorship, libel and slander. Revues were just the beginning: the satircal rag Private Eye, a fashionable club called The Establishment, the controversal BBC show This Was the Week that Was, and some landmark cross-pollination with performers from the United States (Lenny Bruce in particular) took comedy in many new diretions. The resultant legacy paved the way for the proliferation of comedic expression of the next few decades - some, including Carpenter, would suggest an abundant over-proliferation - and allowed most of the personalities involved to have meaningful careers in television and film.

Carpenter knows the bold task before him: rescue an under-researched period of British cultural history from obscurity, in the process convincing many of its principle players that their achievements were far more significant than even they thought, all while staying within the confides of defensible scholarship. For the most part, he does a wonderful job. The stories of how satire rose and fell are mostly culled from anecdotal chimings by the comedians under scrutiny, but at times their memories leave cloudy pictures of what really happened. In the end, the possibilities of satire are but one part of a larger matrix that included the literature of the "Angry Young Men," the films of the (confusingly, perhaps unfairly named) British New Wave, the fallout of cultural revolutions of various stripes, and a general youthful world-view that supercedes the dreary past. His defense of the histories of the satirists against, say, the filmmakers (toward the end of the book) seems a little unwarranted. He need not question the value of his work, but rather, if any major criticism could be levelled against it, could have continually weaved a broader cultural web instead of leaving it all for the end. Recommended reading for persons interested in British cultural history, the history of comedy, and narratives of success in the arts.